The Forgotten Revolutionary: Shaheed Arif Hussain Al Hussaini and his Revolutionary Struggle

In this post, Qalbe Hasnain explores the often overlooked political struggle of Shaheed Arif Hussain Al Hussaini, whose revolutionary spirit awakened the political consciousness of the Shia of Pakistan.

“Religion should be the axis of politics, politics should not be the axis of religion.”

Allama Arif Hussain Al Hussaini was born on the 25th of November, 1946 in the village of Pewar of Parachinar in the Kurram Agency of the province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. He belonged to a very respectable family of the Doerazai Tribe, a tribe that was the descendant of the 4th Shia Imam Hazrat Ali Ibn Hussain Zain-ul-Abideen (a). He received his primary education at his hometown's government primary school, and later on completed his matriculation in Parachinar. Later, he showed interest in religious studies and got admitted to Madressa Jafria, Parachinar, from which he went to Najaf to further his studies. In 1973, He returned home, got married, and in 1974 went back to Qom to join the Hawza there.

While Martyr Allama Arif Hussain Al Hussaini was studying in Najaf, Imam Khomeini (ra) was also living in Najaf in exile. Imam Khomeini (ra) used to lead Maghribayn prayers at the Madressa of Ayatollah Burujerdi. Very few Muslims used to pray behind Imam Khomeini due to the strict vigilance over him. But the only Pakistani who, without any fear, came every evening to pray behind Imam Khomeini (ra), was Martyr Allama Arif Hussain Al Hussaini. After the prayers, Imam Khomeini (ra) would deliver a lecture. The martyred Allama was said to have listened to every lecture with complete concentration and focus. After returning from the lecture, he used to repeat what he learned to his fellow students in the hostel where he used to live, and encouraged them to attend the lectures of Imam Khomeini (ra). [1]

His political struggle started in Najaf, where he faced continuous harassment at the hands of the Iraqi dictator, Saddam Hussein and his authorities, but that wasn’t enough to stop him from achieving his aspirations. Because of his attachment to Imam Khomeini (ra), he was ordered to leave Najaf. He chose Qom as his next destination, where revolutionary activities had peaked. Due to his political activities, he came under the eyes of the Shah’s intelligence and was arrested, threatened and tortured, but he remained determined. Imam Khomeini (ra) gave him his Wikalat Nama, (a letter issued by a Marja to a student to issue fatwas and collect Khums in his name) but it was seized at the border of Iran in 1983 when he was returning back to Pakistan.

On his return back to Pakistan, he started his political activities by giving speeches in local Shia mosques. He also founded the Shaheed Foundation to protect the welfare of the families of martyrs. His first clash with the dictator of Pakistan, Zia ul Haq, happened when a committee of ‘Maliks’ (political agents) was created by his government to look after the affairs of the area. Martyr Arif spoke openly against this committee, and called for the Malik’s assembly to be abolished to put an end to their oppressive monopoly, which led to his arrest. After this event, his popularity sky-rocketed at the expense of the Khurram agency's imperialist agents, who grew concerned by this.

In 1984, Martyr Arif was elected as the leader of Tehreek-e-Nifaz-e-Fiqh-e-Jafria (TNFJ), a political party representing the Shias of Pakistan, which marked the beginning of his political struggle in the country. Peshawar became the headquarters of the party and from there, they visited other areas all over Pakistan and gave speeches tackling the misconceptions about Shi’ism and its adherents. Under the context of growing ethnic violence and sectarianism in Pakistan, Martyr Arif called for the people to instead be united and direct their efforts against the tyrannical dictator. He also educated the masses about the crimes of the USA in the region and raised anti-imperialist slogans. These efforts awakened the political consciousness of the Muslims of Pakistan, developing what could be called the spirit of revolution across the country, and led to Imam Khomeini (ra) issuing a written statement appointing Martyr Arif as his official representative in Pakistan. Martyr Arif held a press conference in Peshawar demanding a change in the corrupt political system through the removal of Zia ul Haq from power. Growing in insecurity, the dictator and his agents began a series of targeted attacks against the Shia of Pakistan. Muharram processions were stopped, banned, and attacked, but this did not stop Martyr Arif from his struggle against oppression. He continued to advocate for Muslim unity and throughout his life, united them under one banner.

Martyr Arif welcoming Ayatollah Khamenei during his visit to Pakistan

The increasing popularity of Martyr Arif among the people in Pakistan was seen as a threat by the imperialist agents, especially through the famous Quran-O-Sunnat Conference in 1987 which shook every imperialist puppet, as it was attended by more than one million people of different sects from all over Pakistan. No one had seen such unity among the Muslims against the dictator in these numbers. It was later confirmed by a senior journalist that all newspapers related to the conference were taken by the US embassy in Islamabad, while many recordings of the program were sent to the US.

The environment of revolution in Pakistan was being solidified by Allama Arif, which became too much to bear for the corrupt officials. On 5th August 1988, after finishing his Fajr prayers, two gunmen entered the Madrassah and assassinated the scholar. Those behind the assassination of Martyr Arif were unknown until the involvement of Captain Majid Jilani, an army officer in the protection team of Zia ul Haq, was later revealed.

‘The loyalist and lover of Islam and its revolution; the defender of the oppressed and deprived; son of Syedul Shohada Aba Abdillah Al Hussain (AS). We should think deeply by putting the example of martyr Syed Arif in front of us. There is no greater achievement for the pious than to leave his abode with wounds that are medals on his chest, and his face covered in blood, in the struggle for justice, and in the highest stage of piety. He inspired thousands of other thirsty people to drink this beverage of light. Pakistan’s blessed people are from a pro-revolution nation. They aspire to live according to Islamic rulings, with which we have an ancient, deep, and faithful relationship. It is imperative for them to keep martyr Syed Arif’s thoughts alive and to pass his message on. Nonetheless, the road to fight against American Islam is very difficult and puzzling. Therefore, it is necessary that all possible factors should be made clear for the impoverished Muslim masses. If this work would have been done through Islamic schools then there is a high possibility that he, Arif Hussain Al Hussaini would be living amongst us today. So now it’s necessary for us to fight against the western and eastern tyrants with all courage and understanding. I have lost my dear son.’

- A message from Imam Khomeini (ra) on the martyrdom of Allama Arif

Even after decades have passed since his martyrdom, the Shias of Pakistan have been left with a feeling of being orphaned, as no leader has been able to work for the welfare of people and lead the banner of unity in Pakistan like him.

Sources used:

[1] https://www.erfan.ir/english/80560.html

*Author note: The Majority of sources used in this article have been taken from Safeer-e-Noor by Tasleem Raza Khan - a book on the life of the Shaheed which is currently only available in Urdu.

Edited by Aymun Moosavi

The Case for Armed Resistance: Where ‘Peaceful Coexistence’ Was Not Enough

Exploring the armed struggles of the ANC in South Africa and FLN in Algeria during their settler-colonial occupations, this post explores the justifications for and merits of armed resistance, while touching on the work of Fanon.

Throughout history, armed resistance has been viewed with scepticism. So-called ‘peaceful’ solutions, which are often an excuse for inaction, have been preferred by onlookers. But these calls are often overshadowed by one glaring issue, which is that the coloniser and the colonised do not share the same notion of peace.

The misplaced pacifism in today’s discourse has dampened the validity of armed struggles against the occupiers of today, like that of Palestinians’ against the Zionist regime. Even those who voice support for Palestine semantically evade the question of an armed struggle as if the use of it would affect the palatability of their resistance.

As exemplified most recently by the worldwide reception of civilian-led resistance in Ukraine, with weapons and homemade Molotovs in hand, the dislike for armed resistance has never been a question of morality - it is rather one based on selectivity; on who is and isn’t allowed to engage in these acts based on their appearance and what they symbolise. What can be understood even by this selective support is that we all possess an innate moral understanding that the weight of oppression can be justifiably relieved by any means necessary including force - so long as the people being oppressed are deemed worthy of doing so.

What is made abundantly clear about those who adopt this selective approach is that they are not concerned with liberation; they are concerned with its readability and how morally acceptable it appears, despite the parameters of what is wildly changing depending on whose armed resistance is under discussion.

Far from being an inadequate solution, the historic record of successful armed liberation movements has proven that it can be more than just a viable option; it can be a necessity to dismantle colonialism, to combat what is in essence a form of violence itself. In this post, we touch on the work of Frantz Fanon while exploring some of the examples of armed resistance in settler colonial contexts to understand its applicability, and how it is a morally justifiable solution to dismantle colonialism even today. Though there are countless examples of this stretching from Cuba to Vietnam, for the sake of time we focus on unpacking the armed struggles of the ANC in South Africa and the FLN in Algeria.

Exploring the Alternative: colonial responses to non-violence

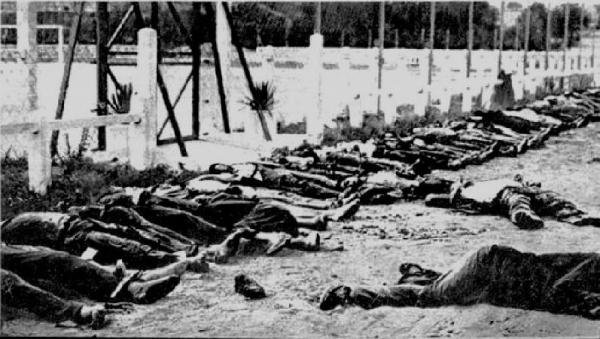

It’s often the response to non-violent resistance which paves the way toward an armed struggle. This was the case for Algeria in 1945, after the Sétif and Guelma Massacres. The French had broken out into celebrations during the victory of the allied forces at the end of World War 2, at the same time that thousands of Algerians were growing in anti-colonial sentiment after years of brutal treatment. Many Algerians took to the streets, peacefully protesting for civil rights, and the right to independence which was promised to them by the French on the condition that they aided the French during the war through service. As the number of Algerian protesters increased, so did French anxieties. French troops were ordered to attack with disproportionate force; they began firing into the crowds, killing unarmed civilians. Fighting between the two groups intensified as the French pillaged through villages in ground offensives, and carried out aerial bombings, massacring thousands. Though numbers range, it is estimated that over the span of a few weeks, up to 45,000 Algerians had been killed.

In many ways, these massacres formed the basis of the armed struggle in Algeria, as it amplified the hypocrisies of the ‘civilising mission’ of French colonial rule, as well as their disregard for Algerian life. It became a catalyst for the War of Independence and formed the revolutionary spirit of those who would later lead them in their fight, such as Ahmed Ben Bella who would later become the face of the FLN’s armed struggle. He came to the realisation through this event that the French had no interest in compensation or compromise, and would have to be fought with force.

***

Before turning to arms, the ANC had adopted a more muted approach to the struggle against apartheid. The organisation was initially created in 1912 and was committed to restoring the right to vote for black and mixed-race South Africans through nonviolent, peaceful protest. So what was it that caused the turn to armed resistance?

One event was the Sharpeville Massacre of 1960. As part of the Defiance campaign, members of the ANC and other groups began protesting through non-violent acts of civil disobedience. One such method was Pass-burning. Passes were an internal passport system enforced by law to facilitate segregation. Black South Africans were made to carry passes at all times which among other things, limited their movement and their ability to travel and work, essentially treating them as second-class citizens. The police responded to the non-violent protest by opening fire on the crowd, savagely killing around 69 people while leaving many others injured.

This act was done under a backdrop of tightening colonial control which severely affected the black population's quality of life. Black South Africans were unable to own or rent real estate outside of areas designated to them, and shanty towns on the outskirts of major cities were growing as black South Africans were prevented from living in the cities. Black labourers were banned from managerial positions as well as trade unions, creating no prospect for career progression or job security. Surveillance, killings and imprisonment of activists continued. With thousands of activists behind bars and conditions worsening, people began to feel apathy towards the ANC, as their efforts were not creating any substantial change to the apartheid, Manichaic system. Even the sole goal it had set out to do in 1912, to reinstate the black voting rights, had not yet been realised.

While some believe that talks of armed resistance began long before Sharpeville, others see it as the main turning point. Soon after the massacre, 2,000 activists were imprisoned and the ANC and PAC were outlawed, forcing many members to go underground.

Here, the colonial system showed clearly, as it has always done, that it did not care for the concerns of its subjects, even when they were wrapped in peaceful packaging. Non-violent resistance is usually proposed under the assumption that the perpetrator is reasonable; that it has the capacity to yield to the needs of the ones it suffocates, and that it wants to exercise this ability. However, as Fanon suggests, a colonial system cannot be treated as if it has reasonable, humane, and logical faculties:

“Colonialism is not a thinking machine, nor a body endowed with reasoning faculties. It is violence in its natural state, and it will only yield when confronted with greater violence.”

- Frantz Fanon, Wretched of the Earth, [2]

It was under these brimming conditions that, true to Fanon’s words, the then President of the ANC’s Youth League Nelson Mandela along with his colleagues came forward voicing a desire to pivot from non-violent protest to armed resistance. He voiced the feelings of those who were increasing in apathy towards non-violent resistance:

Snippet of Mandela’s first TV Interview with ITN, 1961 // Link to interview

Within Mandela’s conclusion, we see a nod towards something mentioned by Fanon who suggests that within the Manichaic life that colonial systems produce, it is the natives' realisation of his own humanity that allows armed resistance to become a more palatable option:

“At times this Manicheism goes to its logical conclusion and dehumanises the native, or to speak plainly, it turns him into an animal…The native knows all this, and laughs to himself every time he spots an allusion to the animal world in the other’s words. For he knows that he is not an animal; and it is precisely at the moment he realises his humanity that he begins to sharpen the weapons with which he will secure victory.”

- Frantz Fanon, Wretched of the Earth [1]

This marked a change in the understanding of effective resistance. It was the realisation that non-violence in response to systemic, violent oppression, would simply not work to dismantle violent apartheid practices that were so deeply interwoven into the state system. This weaving went beyond the psyche of the State and into its institutions, emboldening them to see its subjects not as humans, but as things that could be controlled, herded and killed if they rebelled. It was the realisation that an oppressor, whose existence is fuelled by violence, will not see or appreciate the humanity behind non-violent resistance.

Learning from the aggressor: making life unbearable for the coloniser

In Algeria, continued colonial suffocation led to the formation of the National Liberation Front (FLN) which would lead the fight against the French in the brutal War of Independence in 1954. The period of non-violence had largely come to an end as the FLN had propelled itself into an all-out armed struggle, in pursuit of a sovereign Algerian state. The FLN carried out strategic bombings and became sophisticated in their use of guerrilla warfare against the French, which would later become an inspiration for others revolutionaries like Che Guevara. Fighting was brought to the cities which increased international and domestic pressure on the regime, and a general strike was issued, which caused great economic damage to the regime.

Strikers marching the streets of Algiers, 1957

Echoing the years prior, the French responded with brute force. They used tactics like napalm, torture, forced labour in concentration camps, and mass rape. Psychological warfare also became a key tactic for the French by targeting FLN family members and causing false flag events where turned FLN members would cause havoc to frame the FLN, in order to spark distrust and fear among the public.

Similarly in South Africa 1961, shortly after the Sharpeville massacre, the ANC’s armed struggle began under the armed wing of the organisation called MK, and was mainly coordinated by Mandela himself from underground cells. The attacks escalated quickly over the years from sporadic blows to a systematic, sophisticated attack which overwhelmed the colonial system. The MK went from coordinating 11 attacks mainly on railway lines in the year of 1977, to a serious escalation in the 80s where at least one attack was carried out a week on police stations and strategic installations. The years in between were no different - methods of armed resistance continued, including car bombings, shootings and sabotage, while new members were trained in guerilla warfare with the help of the FLN of Algeria, and the rebels of the ongoing decolonial struggles in Cape Verde, Angola, and Mozambique. These attacks shook the regime, striking fear in the settlers all the way up to government officials who could no longer suppress the resistance as easily as before.

As Fanon suggests, violence can only be quelled with greater violence. It is a tactic that is learned from the colonisers themselves, who show that there is no other way to bargain than through threat. The notion of peaceful conflict resolution where both parties are left content, as is often proposed by onlookers requires two things; that the colonial power is interested in compromise, and that the colonised are willing to sacrifice some of their basic freedoms in order to respect that. Believing the former would negate everything we have come to know about exploitative colonial rule that is only made to aid the interest of the colonial state, while the latter is simply unfair when basic rights are in question. The only thing that the colonial power will bend to is a sizeable threat - one that has the potential to get in the way of their interests. In order to form a sizeable threat, one can and should work in the same language of the coloniser, and that is violence.

Armed Resistance and its bargaining power

This new kind of resistance in South Africa had given activists a form of leverage that had not been enjoyed before. Rather than stifle the resistance after Mandela’s imprisonment in 1967, it gave the resistance bargaining power. Foreign investors became increasingly reluctant to pour their wealth into the country as political instability continued, and foreign leaders like Margaret Thatcher were forced to tell the regime to enter into negotiations with the MK and release Mandela under domestic pressure. This international pressure, coupled with the increasing domestic chaos caused by the MK pressured the South African government to enter into talks with the MK. Under the leadership of Botha, Mandela was offered release on the condition that he denounced violence as a political weapon and ordered the MK to halt the resistance. Mandela refused:

“What freedom am I being offered while the organisation of the people remains banned? Only free men can negotiate. A prisoner cannot enter into contracts.”

- Nelson Mandela

The violence escalated, and under the leadership of De Klerk who was keen to protect South Africa’s international reputation, Mandela was again offered release in 1989, only if he was to denounce communism and again reject the use of violence as a political weapon. Mandela again refused, stressing the importance of armed resistance as a bargaining tool. As violence once again increased and international pressure boiled over, the government was left with no choice but to succumb to the conditions of the resistance. On the 11th of February 1990, Mandela was released from prison, and ANC was legalised.

Nelson Mandela & his wife Winnie Mandela, shortly after his release from prison on 11th February, 1990

Through this, we see how armed resistance can give leverage to the anti-colonial struggle. Mandela was able to bargain largely because of the threat of violence which became too much to bear for the colonial regime, and forced them to bend to the needs of the resistance. It packaged the struggle in a language that the coloniser would understand and was all too familiar with which was the threat of force, and what ultimately led to the success of the resistance.

***

Conclusion

Armed resistance occurs alongside the realisation of the humanity of the native, by the native, while living under the Manichaic system that colonial regimes impose on them. It is an awareness of the fact that they cannot be herded like animals, massacred, or deprived of basic rights, and that when that does happen, they have every right to fight back. As suggested by Fanon, this is often forgotten by the native, whose memory of his humanity fractures after the decades, even centuries-long attacks by the colonialists which take both psychological and physical forms, and seek to dehumanise and break him down completely. But often times this memory is pieced back together with the help of the colonialists themselves, whose aggressive and violent response to non-violence & peaceful protests angers the oppressed enough to remind them of their humanity, while unveiling the reality that colonial states are not here to compromise and never will with a category of people they seek the exploit. In this way, non-violence is often deeply embedded into the story of armed resistance, as it is often the response of the coloniser to it which convinces the colonised that this method cannot work on its own, as was the case in both South Africa and Algeria.

However, the onlookers of colonial struggles often lose sight of the natives' humanity more so than the natives themselves. They are the ones who become desensitised to the violence of the oppressor, to the dynamic of the coloniser/colonised relationship after years of repeated media exposure, and often force the oppressed to function within the binary of non-violence if they wish for their struggle to have international acceptance and recognition. Looking into the experience of the FLN and ANC sheds light on the settler colonial methods of oppression which are all too familiar today, and how non-violence is not always enough to combat them. It is one of the only methods that the coloniser has shown the capacity to understand, because it is the only one it deals in. This is where we understand the limits to non-violence, and how for an oppressed group who are deprived of basic rights and live under conditions of constant brutality, armed resistance can become the only viable option for freedom.

Sources Used:

[1] Frantz Fanon, Concerning Violence, Wretched of the Earth, p.42-43

[2] Frantz Fanon, Concerning Violence, Wretched of the Earth, p.61

Palestine and the Olive Tree

For decades, Palestinians have relied on symbolic articulations of nationhood to communicate their historic connection to the land of Palestine. The most prominent of these symbols has been the olive tree, symbolising both their rootedness in the land, as well as their resistance against all forms of colonialism which aim to diminish their claim to it. This article will uncover some reasons as to why it has been made it a target of attacks by the colonial regime, and what these have looked like in recent history.

Olive picking, painted by Damin Abdullah

During the ongoing occupation, erasure of Palestinian history has been one of the most persistent forms of Zionist colonial violence. As a result of this attempted erasure, Palestinians have relied on symbolic articulations of nationhood to communicate their historic connection to the land of Palestine. The most prominent of these symbols has been the olive tree, symbolising both their rootedness in the land, as well as their resistance against all forms of colonialism which aim to diminish their claim to it.

Given its importance, it is no wonder why this symbol of resistance has been under constant attack by the regime as in essence, its cultural and economic significance directly attacks the colonial workings of the Zionist regime, which has sought to divide, disunite and weaken the Palestinian population. It’s very existence reinforces their claim to the land, which in turn attacks the Zionist narrative that is built on erasure, making the symbol alone an enemy of the colonial entity. This article will uncover some reasons as to why it has been made a target of attacks by the colonial regime, and what these have looked like in recent history.

Symbolic significance:

Under colonial strategies of fragmentation which divide the colonised society, cultural symbols can play an important role in unifying the colonised under one emblematic sense of nationhood. In the case of Palestine, the Zionist regime has built its colonial structure off of fragmentation policies, which actively seek to prevent the collectivisation of the Palestinian experience. This method has taken many different forms throughout the history of colonial occupation; Palestinians are isolated in restricted areas, some are imprisoned, and others are expelled from the land entirely, losing their physical connection to their homeland.

These policies are enacted to weaken the Palestinian experience, and thus their ability to oppose the colonial structure as a powerful, united entity. In this context, cultural symbols allow Palestinians to unite under one sense of belonging and heritage, reviving the cultural memory of their historic claim to the land under increasing attempts aimed towards erasing it. These symbols contribute to the national consciousness of people living in divided societies, where there are limited means of expression.

The olive tree is an example of a symbol that rekindled this cultural memory at a time when the regime's fragmentation policies were in full force. Olive trees hold a lot of historical significance, as they date back to 8,000 BC, which Palestinians draw connections to to amplify their traditions and ancient presence in Palestine. [1]. Nasser Abufarha suggests that the olive tree gained its symbolic significance once the Liberation movement was crushed in the 80s, when the exiled Palestinian populations in Lebanon lost their strategic position in the struggle for Palestine, as they were pushed into further exile in Tunis and Yemen [2]. The struggle then shifted primarily onto those in the West Bank and Gaza, where the olive tree was already taking hold as a symbol of resistance and rootedness in the land.

Economic security

In addition to its symbolic significance, the olive tree provides Palestinian’s with economic security in the occupied Palestinian territories (oPt). In 2009, it was recorded that around 45% of land in the oPt was planted with olive trees [3], while the olive oil industry more generally provides ¼ of the gross agricultural income in the oPt, supporting the livelihood of approximately 100,000 families. [4]

In this way, it could be said that the olive trees’ economic significance contributes to its symbolic significance, as any acts surrounding it including the planting, harvesting and general tending to the olive tree, become politically charged acts, aimed at safeguarding the oPt’s prosperity against the colonial occupation's disruption.

Understanding the economic and cultural significance of the olive tree provides a useful backdrop to grasping the motivation behind the regime's frequent attacks, and why they have increased significantly in recent years.

Colonial sabotage and exploitation

1. Uprooting trees

The regime has employed multiple methods of disrupting the prosperity that the olive tree provides Palestinians, attacking it as both an economic resource, and a symbol of resistance. A mass uprooting of trees occurred in 2002, in order to create space for the construction of the Separation Barrier [5], a key tool for the continuation of colonial apartheid.

The uprooting of olive trees for the expansion of Zufin, a Jewish settlement in the Tulkarm district // Image: Braverman article

This move was justified by a need to promote national security. To quell the outrage caused by the uprooting, it was promised that these trees would be relocated and replanted in new locations once consent was provided by the owner. This however, proved futile, as most Palestinians have no access to any other land, and have instead been witness to the regime replanting the olive trees on ‘Israeli’ land [6]. Here, a key articulation of Palestinian identity, nationhood and livelihood is not only stripped from the owner, but appropriated by the regime under the guise of national security.

2. Settler attacks on the olive groves

This violence extends far beyond the state, through the IOF and settlers who frequently pillage and vandalise the olive groves, especially during harvest season. Together, they have destroyed more than 165,000 olive trees, which has led to an economic loss amounting to $50,849,265 [7].

As recently as last Thursday, 9th December 2021, settlers from the illegal settlement of Mitzpe Yair, backed by IOF forces, chopped down 70 olive trees in the village of Masafer Yatta and led a herd of sheep onto a Palestinian farmers land to destroy its crops, leading to confrontations [8]. It’s been suggested that since the harvest season began on the 4th of October, this year alone 3,000 olive trees have either been damaged or had their harvest stolen [9].

3. Restrictions on social mobility: the permit and timetable system

Colonial sabotage and exploitation has taken on more discrete forms, such as through the permit and timetable system which was put in place for “olive protection,” but in reality has expanded the reach of colonial surveillance and restrictions on social mobility.

Both systems severely limited the economic prosperity for Palestinians in oPt, as they limit Palestinian access to land. At least 40,000 dunums of olive trees were declared military zones, forcing Palestinians to obtain permits that would give them access to their fields for a limited number of days [10].

In Samara, protection is only offered when military timetables are complied with, alienating “Palestinians from local time” by only allowing harvesters access to fields between specific dates that do not account for the time it takes to harvest [11].

Considering that colonised societies more generally are heavily reliant on agriculture as their main economic sector, the effects of Zionist domination have been severe; as stated by the PLO’s National Affairs Department, these expanding spatial restrictions have “provoked a sharp decrease in the agriculture sector's contribution to GDP in the occupied Palestinian territory, from 36% in 1970 to 9.5% in 2000. In 2019, it was less than 3%.” [12].

Here, under the guise of protection, the regime has expanded the reach of its surveillance apparatus, which constricts Palestinians’ sense of time and autonomy over their own land.

Conclusion:

Under the context of fragmentation policies which have sought to fragment and weaken the collective strength of the Palestinian experience, the olive tree acted as a uniting force which symbolically drew all Palestinians together under the same struggle, despite forceful attempts to divide them, which further inspired their narratives of resistance. Economically, the olive tree has brought with it an industry that has sustained the livelihoods of many in the oPt. This cultural and economic importance is only heightened by Zionist attacks, as this alone has given the olive tree another layer of symbolic meaning; under the context of colonial violence, everyday acts of planting, tending and harvesting the olive tree have become in essence, acts of resistance.

These examples of violence against the olive tree on both a societal and state level have highlighted a characteristic theme of the Zionist regime; there is no ‘national security’ or ‘Israeli’ state that does not involve the deliberate plundering of Palestinian resources, economy and culture. Their own colonial policies, including those undertaken to promote national security and so-called “olive protection,” prove that the two cannot find peace in co-existence; there can be no Zionist state alongside a Palestinian state, when the former necessitates full control of, and impediment to, the latter’s ability to not only flourish, but to simply exist.

The olive tree has provided Palestinians with a narrative of both heritage and resistance. It demands that attention be given to the Palestinian right to exist independent of their colonial occupiers, making it on its own a powerful symbol in opposition to the regime.

Sources Used:

[1] Land of symbols: cactus, poppies, orange, and the olive trees in Palestine, Nasser Abufarha, p.353

[2] Ibid, p.352

[3] Uprooting identities: The Regulation of Olive Trees in the Occupied West Bank, Irus Braverman, p.240

[4] Olive Harvest Fast Facts, The Question of Palestine, OCHA

[5] Braverman, p.240

[6] Ibid, p.249

[7] Israel's Hegemony Explained: The Case of Palestine’s Olive Harvest Season, PLO Negotiations Affairs Department (NAD)

[8] ‘Israeli settlers chop down 70 olive trees, let loose sheep to destroy Palestinian farm,’ Middle East Monitor

[9] Ibid

[10] NAD

[11] Braverman, p.257

[12] NAD

Necroviolence in Palestine

In light of the Zionist regime’s announcement of its plan to demolish part of the centuries old Al-Yusufiya cemetery for the construction of a national park, this article discusses the forms of necroviolence inflicted on Palestinians through the decades, exposing its effects and consequences on Palestinians long after death, when it is backdropped by colonial occupation.

Mother of Alaa Nababta clings to her sons grave at Al-Yusufia Cemetery, resisting the IOF’s forceful attempt to remove her // Source: Mostafa Al-Kharouf

The Zionist regime’s announcement of its plans to demolish the centuries old Al-Yusufiya cemetery for the construction of a national park sparked widespread public outrage last month.

However, it is important to understand that this act was not an isolated event, but rather one reflective of a pattern characteristic of colonial rule, whereby the colonised populations’ heritage, history, and identity are violated by the coloniser, sometimes long after death.

This article will draw on the framework of necroviolence to bring these patterns to light, and to further uncover the discriminatory ethos embedded deep within the Zionist regime’s character, which justifies the execution of these violent attacks against every aspect of Palestinian existence.

What is necroviolence?

The concept of necroviolence finds its origins in the theory of necropolitics first coined by Achille Mbembe, a political theorist. In his words, Necropolitics explains “the ways in which, in our contemporary world, weapons are deployed in the interest of maximally destroying persons and creating death-worlds, that is, new and unique forms of social existence in which vast populations are subjected to living conditions that confer upon them the status of the living dead.” [1]

In his book, Mbembe argued that the clearest example of the manifestation of necropower today is the Zionist colonial occupation of Palestine. From surveillance to outright apartheid, the regime exerts full control over the conditions in which Palestinians both live and die.

Necroviolence however, takes this theory one step further. Building off of Mbembe’s theory, Jason De Leon brought forward the concept of necroviolence which would take this theory beyond the boundaries of death. He defines it as:

“Violence performed and produced through the specific treatment of corpses that is perceived to be offensive, sacrilegious, or inhumane by the perpetrator, the victim (and her or his cultural group), or both.”

- Jason De Leon in The Land of Open Graves, p.69 [2]

His theory goes beyond how states assign different values to human life, to offer insight into what happens once this judgement results in the death of individuals from the ‘inferior’ community.

Necroviolence then, is the recognition that violence against a certain community can extend far beyond death, which allows us to draw out both the effects of this form of violence on the community that identify with the dead, as well as the characteristic condition of the perpetrator which justifies this corporeal mistreatment.

The Zionist regime’s use of necroviolence

1. ‘Ambiguous loss’; withholding Palestinian bodies

Since 1967, the Zionist regime, has been preventing Palestinian families from mourning their loved ones by withholding their bodies in freezers, [3] or the ‘cemetery of numbers’ (discussed below). This form of necroviolence, which imprisons the already dead, forces Palestinian bodies to exist in a state of absence; their location, status, and condition are often unknown for an indefinite period of time.

A mother stands at the empty grave of her son in the occupied West Bank. The regime has refused to hand over his body // Source: MEE, Shatha Hammad

This act in itself can be viewed as a form of collective punishment aimed at the families of the martyrs, who are forced to endure a great level of psychological pain in addition to grief over the loss of their loved ones. The colonial regime thus punishes families left behind for the mere existence of their martyrs, who represent Palestinian resistance as a whole.

“The erasure of a body… stunts the development of the social relationships that the living need in order to ‘make sense of the life and death of the deceased’ and negotiate (and renegotiate) the positions of the dead inside the living community.”

- Jason De Leon in The Land of Open Graves, p.71 [4]

Many families are then left in a state of what psychologist Pauline Boss calls 'ambiguous loss’; “a loss that remains unclear” [5], as their grieving process is forcefully halted by the regime's withholding of information which would allow families to carry out the cultural mourning process. By doing this, the Zionist regime alters the bereavement period by dictating when and how Palestinians should be mourned.

2. The cemeteries of numbers

‘Ambiguous loss’ can also be felt through the existence of the Cemetery of Numbers where mass graves of Palestinian martyrs are located, who are identified only by a numbered metal plate above their grave.

The Cemetery of Numbers // Source: The Palestine Chronicle

This marks an attack on the Palestinian experience, with the erasure of their names and the possibility of mourning, as well as a dehumanising attempt to erase individual identity by collectivising the Palestinian experience under nothing more than numbers.

Though in complete violation of human rights by international law, these bodies are kept as leverage for potential political negotiations with Hamas or the PA and as a deterrence from resistance to the occupation, further tormenting families who are left to campaign for the right to bury their loved ones days, months, and often years after their death. In 2019, the Israeli High Court approved the withholding of these bodies on the basis of state security, civil order, and the carrying out of political negotiations [6].

Here, we see the politicisation of Palestinian bodies, as they are used to maintain the colonial system, forcing martyrs to exist within the occupier-occupied dynamic long after death through the policing and dispossession of their bodies.

3. Demolition of historic gravesites

The Zionist regime has made the demolition of cemeteries a key arena for necroviolence to facilitate colonial expansion and historical erasure.

Mamilla cemetery - an ancient Muslim burial site located in Jerusalem, which dates back 1,400 years, has been one of the many burial sites under persistent attack by the Zionist regime. This cemetery in particular held the bodies of many of the early companions of the Prophet (pbuh), as well as Christians from the pre-Islamic era [7]. In the 80s, part of the cemetery was razed to build a municipal parking lot, while in 2004, it was announced that part of the cemetery would be demolished to create the Museum of Tolerance to commemorate the Jewish Shoah [8]. Bab Al-Rahmeh has faced the same fate, as large sections of the cemetery were levelled to build a park and hiking trail [9].

More recently, the Zionist regime announced its plans to demolish Al-Yusufiya cemetery - another burial site with great religious and historical significance. It was decided that a large portion of the cemetery would be razed in order to build a national park, which will open mid-2022. Public outrage soared last month, as images and videos circulated of Palestinian families clinging onto their loved ones' graves to protect them, while being confronted with stun grenades, beatings and arrests by the IOF [10].

A Palestinian shows the destruction of graves at Al-Yusufiya cemetery by the Jerusalem municipality and the Nature and Parks Authority // Source Ahmad Gharabli

As Jason De Leon suggests;

“The destruction of a corpse constitutes the most complex and durable form of necroviolence humans have yet invented. The lack of a body prevents a “proper” burial for the dead, but also allows the perpetrators of violence plausible deniability.”

- Jason De Leon in The Land of Open Graves, p.71 [11]

The regime has not only prevented the burial of Palestinian bodies, it has also gone to the extent of attacking the already buried, violating their bodies for further territorial expansion.

This also marks a step towards the complete erasure of the Palestinian experience, as many of these grave sites are centuries old, holding within them not only a history of Palestinian belonging, but one of resistance through the presence of martyrs who resisted decades of occupation.

The Zionist regime thus denies Palestinians agency in one of the few forms it has left to exercise; that is, the traces of their heritage, identity, and history on ground.

Conclusion

Here, we gain insight into the logic of Zionist colonialism, which necessitates full control over every aspect of the Palestinian individual, both in life and death; in all forms of existence.

This then, has grave consequences for the families of the martyrs, as the direct and indirect targets of most forms of necroviolence are the living community. The body is not treated as an individual. To the coloniser, the body is a national body representative of the enemy; the colonised group as a whole. It is they who have to endure punishment for their martyrs resistance, and often, just for their mere existence.

In this way, the regime’s exercise of necroviolence is a confirmation that Zionist colonialism continues long after death, through the dispossession, policing, and politicisation of Palestinian bodies, as well as territorial expansion through historical erasure. Erasing all traces of Palestinian culture, heritage, and identity works as an attack on the legitimacy of the Palestinian experience, allowing the regime what Leon called “plausible deniability,” and is therefore one of the key mechanisms with which the Zionist regime can continue its colonial rule.

Sources Used:

[1] Achille Mbembe, Necropolitics

[2] Jason De Leon, The Land of Open Graves, p.69

[3] Suhad Daher-Nashif, Colonial management of death: To be or not to be dead in Palestine

[4] Jason de Leon, p.71

[5] Ibid

[6] Lina Alsaafin, Israel slammed for ‘necroviolence’ on bodies of Palestinians

[7] Randa May Wahbe, The politics of karameh: Palestinian burial rites under the gun, Randa May Wahbe p.329

[8] Ibid

[9] Ibid

[10] Samah Dweik, Palestinians vow to defend graves in Jerusalem cemetery

[11] Jason De Leon, p.71

The Flawed Application of ‘Normalisation’ for Peace Building in Palestine

Amongst the media storm that followed the 11 day Israeli massacre carried out in Gaza this past May, calls for a peaceful solution to end the bloodshed have been heard louder than ever before. Built off of an ill-informed understanding of ‘normalisation', many such solutions have come and gone, and where applied, produced more disastrous consequences than they came to solve. So what exactly does this term ‘normalisation’ mean, and who does it serve?

Yasser Arafat and Yitzhak Rabin shake hands outside of the White House after agreement over the Oslo Accords (1993).

Amongst the media storm that followed the 11 day Israeli massacre carried out in Gaza this past May, calls for a peaceful solution to end the bloodshed have been heard louder than ever before. Built off of an ill-informed understanding of ‘normalisation', many such solutions have come and gone, and where applied, produced more disastrous consequences than they came to solve. So what exactly does this term ‘normalisation’ mean, and who does it serve?

To onlookers who have little to no knowledge on the origins of the state of Israel, and those who have internalised the western understanding of the Palestinian struggle, normalisation would seem to make sense. Calling for two rival states to view each other and their populations as equals, meaning to either shake hands under a new order inspired by an older, more palatable one, or to forget past strategies and proceed with a clean slate. This, they propose, creates a hopeful, promising future for both parties.

However, their suggestion highlights that those who advocate normalisation carry with them the preconceived notion that the two parties involved in a conflict are always equals in ability. Such a stance requires a complete oversight of history - however ugly it may be.

A glance at the historical record of the so-called ‘peace process’ in Palestine- where this term has been habitually misused - allows us to see the problems with seeking ‘normalisation’ in a situation wherein there has never existed a ‘normal’ bilateral relationship. In reality, the relationship is only a contemporary re-configuration of the relationship between the occupier and the occupied. It highlights how this very balance of power affects the terms of normalisation, often tipping it in favour of the more powerful faction.

The next section will develop this discussion.

Normalisation in perspective: a glance into the historical record

The Foundations of the Zionist Regime

If normalisation means the return to better relations, finding a point in history where relations have been satisfactory is a difficult task.

From its very inception, the Zionist state has built itself off the trampling of Palestinian rights. The Balfour Declarations which declared a national homeland for the Jewish people, did so without any Palestinian agreement, though they made up 90% of the population [1]. A series of policies seeking to make this ‘national homeland’ a reality by forcefully displacing Palestinian populations through land grabs and mass displacements, meant that Palestinians have only seen decades of turmoil since the birth of the Zionist regime. There has been no equality of status, nor forms of recompense for the above violations of international law. Thus, seeking to reinstate some form of return to an imagined past where relations were somewhat ‘better’’ is futile, as it never existed to begin with.

This history of violence, expulsion and oppression cannot be forgotten, as it is this history which continues to form the backdrop of any solution to the Palestinian occupation, as well as the Palestinian stance within negotiations. Attempting to deny or erase this reality, as has been done in most peace talks, has only exacerbated the apathy towards them.

The failure of the Oslo Accords

On the other hand, if normalisation means the turning of a new leaf and forgetting the history of Palestinian subjugation, we do not need to imagine what this might look like, since we have seen it in action through the outcomes of the Oslo Accords where the PLO was first recognised by Israel, and the Palestinian Authority first formed.

Under this so-called peace process, the West Bank (WB) was divided into areas A, making up 18%, Area B making up 22%, and Area C making up 60%, of which both areas A and C were supposed to be under full jurisdiction of the PA [2].

In reality though, none of this materialised, with Israel having full external security control over area A and full control of area C, including that of its economy, construction, and development [3], tripling the number of illegal settlements in the West Bank that were maintained by the same oppressive policies used in the years prior - the vast majority of which remain in area C.

In this way, a peace process said to normalise ties between Israel and Palestine, paving the way towards a two-state solution, ended with the expansion of settler colonialism and suffocation of the Palestinian liberation movement, highlighting one of the key failures of policies built off of a flawed application of normalisation. Any policy made in the name of normalisation thus far has tended towards the desires of the more powerful faction, creating no possibility for both parties to talk on equal terms; it is the occupier who has set the terms, and it is the occupier who has reaped its benefits.

American endorsement of the occupier’s status quo

America’s conceptual understanding of normalisation means the negotiation of peace in line with their allies; those who have sustained the balance of power with US help.

Not only was this evident in the Oslo Accords, but more recently in Trump's Middle East Plan which included the establishment of Jerusalem as the capital of Israel, the refusal of the right to return for Palestinians who were forcefully displaced, and the go ahead for Israeli annexation of the Jordan Valley [4] in Area C - a piece of fertile land which was found lucrative for Israeli companies seeking to exploit Palestinian resources, and home to around 65,000 Palestinians [5]. As of 2021, Biden is yet to make any significant changes to these policy implementations.

Normalisation requires an equal playing field for all parties involved; there can be no normalisation where there is no balance of power, especially when we are discussing it in relation to the hierarchical arrangement between occupier and occupied. Yet, as exemplified by these supposed peace deals and negotiations brokered by the West, the meaning and application of normalisation where there are uneven power dynamics is hijacked and gravely distorted by being made with the more powerful faction and its allies in mind.

Conclusion

As the historical record of the peace process in Palestine shows, built into the very essence of normalisation is the silent acceptance and continuation of the Palestinian occupation. This is because we are not using any universal definition of normalisation to integrate into policies, but one that exacerbates the power imbalance by putting the more powerful factions' desire for the status quo to be maintained at the forefront of any deal.

There are lessons to be learned from this history, all of which point to there being little hope for peace between Palestine and Israel when this very relationship is reflective of the colonial power imbalance produced by the occupier-occupied relationship. This is the very problem with solutions built off of this pacifist understanding of normalisation such as the so-called two-state solution, which does nothing to counter this imbalance of power.

Any attempt at ‘normalisation’ would necessitate the complete reintegration of displaced Palestinian populations into their land, governmental control placed back into their hands, and a complete overhaul of the settler colonial system which was imposed on Palestine in 1917. Only once this is achieved will there be any justice done to the kind of normalisation we should aspire to; one that doesn't ignore or minimise the consequences of settler-colonialism, but seeks to entirely collapse this system of oppression.

Sourced Used:

[1] Illan Pappe, ‘The Palestine peace process: unlearned lessons of history'- https://www.historyandpolicy.org/policy-papers/papers/the-palestine-peace-process-unlearned-lessons-of-history

[2] Al Jazeera, Palestine Remix, https://interactive.aljazeera.com/aje/palestineremix/the-price-of-oslo.html#/14

[3] Al Jazeera, ‘What are areas A, B, and C of the occupied West Bank?’ - https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2019/9/11/what-are-areas-a-b-and-c-of-the-occupied-west-bank

[4] Oliver Holmes, et al, ‘Trump unveils Middle East peace plan with no Palestinian support,’ https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/jan/28/donald-trump-middle-east-peace-plan-israel-netanyahu-palestinians

[5] Ian Black, “This ‘deal of the century’ for the Middle East will be just another bleak milestone,” https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/jan/30/donald-trump-israel-palestinians-middle-east

[6] Noam Chomsky & Ilan Pappe, On Palestine

Musa Al Sadr: a Brief Exploration into the Clerics Political Legacy

As part of the political profiles series, this article offers a brief exploration into Musa al Sadr’s contributions to the Shi’i political Awakening of Lebanon.

“Whenever the poor involve themselves in a social revolution, it is a confirmation that injustice is not predestined.”

Image link: Musa al Sadr

The cleric's contribution to Shi’i Lebanese political thought and resistance is hard to miss. Through his charismatic leadership, an entire community was led out of political quietism into active resistance against a negligent government, planting the seeds to what would be Lebanon’s Shi’i political awakening for decades to come.

Sadr, born in the Iranian holy city of Qom to a Lebanese Ayatollah, arrived in Lebanon in 1959. With familial roots in Iran, Iraq and Lebanon, his background automatically tied him to a transnational tradition which ideologically bound the Shia of these areas together, contributing to his respected status across the international Shi’i community, as well as those of Lebanon.

At the time of his political ascendancy in the early 60s, Southern Lebanon was home to the impoverished and destitute Shia minority, which had been a product of years of government neglect that had pushed them to the very bottom of all socioeconomic indicators. Shi’i politics was monopolised by elites and their extensive patronage networks, which excluded average members of society. Though frustration over their neglect began to boil over, the Shias lacked the political organisation and motivation required to challenge these issues.

It was within this context that Sadr found his political calling. The next sections will unpack some of his main contributions to the Shi’i political awakening of the South, and what political legacy this has inspired.

Shi’i political activism

Perhaps one of his most important contributions to political thought was his firm belief in social revolution; to him, change could only be possible if it was a bottom-up, people led movement - one that required political and social organisation, as well as broad based communal support. Political activism was the means through which the impoverished could finally be pulled out of their destitution, giving them the platform to demand change.

Thus, appalled by the socioeconomic conditions of the Southern Shias and their severe underdevelopment, he began his campaign of reform through his role as Chairman of the Lebanese Islamic Shi’i Council, marking the first representative body that gave Shias exclusive representation, independent of Sunni Muslims. Through it, he called for the construction of schools and hospitals as well as wider political reform, which would finally end the period of isolation that cut them off from Lebanese society, and integrate them within its institutions. One of his biggest long term accomplishments was in education, through the establishment of the vocational institute in the Southern town of Burj al-Shimali [1], which has now become an important symbolic landmark of his legacy. He also demanded better military and defence measures that would protect the South from becoming the target of Israeli attacks.

These measures politically mobilised the Shia and improved their aspirations by giving them a new hope that their fortunes could change. He founded new groups concerned with protecting them, such as Harakat al Mahrumin (The Movement of the Dispossessed) in 1974 as well as its military wing Amal (Hope), while ideologically inspired other groups such as Hezbollah. In this way, his teachings have informed the ideological orientation of a generation of political leaders, many of which continue to shape Lebanese politics today. Hassan Nasrallah, the current leader of Hezbollah was one of these men, who at the young age of 16 [2] gained early political experience as a fighter for the Amal movement.

Unity

Sadr proved himself to be a pragmatic leader; though he was primarily concerned with uniting and organising the Shia, he extended his calls for unity beyond sectarian lines to the many different factions of Lebanese society. Harakat al Mahrumin itself, along with Sadr, was founded by Gregiore Hadad, the Greek Catholic Bishop of Beirut. It aimed to be a voice for the oppressed, but was significant in that it did not limit itself to any particular ideology; it aimed to represent all impoverished communities who had experienced government neglect regardless of their ideological orientation. He also gave regular speeches which attracted thousands, in which he invited people to look beyond social divisions and unite to end injustice. It was this pragmatism that allowed Sadr to expand his support base beyond sectarian lines despite his own firm belief in Shia Islam. His approach proved useful in overcoming Lebanon's societal divisions, ensuring the necessary inter-communal support needed to ignite any significant level of change. This approach later informed Hezbollah’s ideology, which has made a point of advertising its support for and protection of Lebanese Christian communities.

A symbolic legacy; ‘the man of double identity’

The controversy surrounding Sadr’s disappearance after attending a conference in Libya in 1978 has bound him to the concept of martyrdom, adding another symbolic layer to his legacy. It was another loss which had struck the hearts of Shias, as his story was now tied to the all-too familiar experience of prominent Shia figures and adherents throughout history; one that typically ended in oppression, sacrifice, and an untimely death. Ayatollah Khomeini, the father of the Iranian Revolution, did not hesitate to make him a representation of sacrifice for a greater cause, to inspire the next generation of Shia militiamen and political thinkers to keep on the path of revolution. Sadr was no longer just a Lebanese reformer, but part of a broader Shi’i tradition that went beyond state boundaries;

“Musa al Sadr himself came to serve an entirely new function. He was a man of double identity, claimed by the Iranians and by the Shia in Lebanon; he embodied the bonds, both real and imagined, between the two.”

- Fouad Ajami in The Vanished Imam: Musa Al Sadr and the Shia of Lebanon. [3]

***

Musa al Sadr's contribution to the Shi’i political awakening of the late 60s and early 70s is incomparable. One man's plight changed the fate of millions of Lebanese Shias who had become nothing but an afterthought before his ascendancy. As a man of great intellect and pragmatism, he was able to toe the line between Islamic-inspired reform and inter-communal unity; between political activism and Islamic spiritual guidance. Through this, he brought a new framework with which to approach issues of the disadvantaged; one that has inspired a generation of political reformers and religious thinkers today.

Sources Used:

[1] Augustus R. Norton, Hezbollah: A Short History (3rd Edition)

[2] Le Monde Patrice Claude, Mystery man behind the party of God

[3] Fouad Ajami, The Vanished Imam: Musa Al Sadr and the Shia of Lebanon

[4] Anoushiravan Ehteshami & Raymond A. Hinnebusch, Syria and Iran: Middle Powers in a Penetrated Regional System

Institutional Racism in the UK: An Overview

Through a brief overview of racial biases within our key institutions, this paper aims to showcase the many faces of institutional racism, from microaggressions to implicit biases, that persist in our institutions in order to highlight the need to actualise the long anticipated change to our institutions that would finally make them cater for and representative of the people they serve.

In collaboration with the Racial Education Project (REP)

Through a brief overview of racial biases within our key institutions, this paper aims to showcase the many faces of institutional racism, from microaggressions to implicit biases, that persist in our institutions in order to highlight the need to actualise the long anticipated change to our institutions that would finally make them cater for and representative of the people they serve.

Guy Smallman // Getty Images

Initiatives to combat racism in the UK have been greatly undermined by the popular notion that it simply does not exist within our institutions. As a neglected norm that has been repeatedly left out of public conversation, racism has now taken on new forms which remain largely implicit, giving it the ability to mask itself within our institutions as nothing more than normality. A combination of micro-aggressions and implicit biases which have been so deeply ingrained within our institutions seem to have contributed to this, allowing prejudicial behaviours, which lead to very real consequences for minorities, to be considered somewhere between ‘normal’ to ‘non-existent.’ This, unfortunately, has resulted in shared experiences of social exclusion & isolation among minorities who bear the brunt of all of its facets, including stifled job opportunities and capped progression in working environments. Patterns of discrimination should therefore be addressed in order to more adequately protect, support, and serve minorities who have been effectively subordinated by our institutions. In order to comprehend the full extent of racial discrimination, this paper aims to distill some key flaws that both expose and encourage the discriminiation towards minorities to go unchecked. Rather than viewing racism as confined to any historical period, it may be time for us to reconsider the failures of our employment, criminal, healthcare, and educational institutions in adequately supporting BAME groups in the UK. This would not only supplement the much needed call for institutional reform, but encourage the full integration of minorities into them, allowing the institutions themselves to perform to a much higher standard.

Institutional racism: An Overview

In order to detect and combat institutional racism, we must first start with a definitional overview of the topic at hand. The Macpherson report published in 1999, a landmark case in exposing prejudicial tendencies within our institutions, categorised the term ‘institutional racism’ as:

“The collective failure of an organisation to provide an appropriate and professional service to people because of their colour, culture, or ethnic origin. It can be seen or detected in processes, attitudes and behaviour which amount to discrimination through unwitting prejudice, ignorance, thoughtlessness and racist stereotyping which disadvantage minority ethnic people.”[1]

Many of these “behaviours” exist because of the persistence of implicit racial biases and microaggressions within our institutions, which remain covert in nature. The problem with these forms of racial discrimination lay in their names; its ‘micro’ and ‘implicit’ qualities prove difficult to detect at face value because of its covert nature, allowing it to be viewed as a sporadic rather than systemic issue. It must be understood however, that this difficulty in detecting and effectively monitoring racism does not negate its presence in our institutions; they can still play a role irrespective of a specific intent to racially discriminate. According to the report, these problematic beliefs are largely a result of the cultural ethos [2] produced in these institutions which act as subconscious cues that determine the treatment of minorities. There is a tendency to expect racism to display itself blatantly with clear overt consequences, but this undermines those consequences that can be passive in nature, like the neglect, lack of understanding, or as stated above, subconscious cues which negatively stereotype minorities, differentiating their treatment within these institutions from others.

As the report highlighted, “The debate about defining this evil...is cathartic in leading us to recognise that it can occur almost unknowingly, as a matter of neglect, in an institution” [3]. After years of debating its definition, it is now time to employ a more organised and systematic effort to detect, monitor, and prevent these glaring issues. This action would begin with a clear outline of where some of the many forms of racism, both explicit and implicit, can be found within our institutions, which will be discussed in the following sections.

Institutional Racism Within the Criminal Justice System

Policing

One of the more explicit forms of racial discrimination against BAME groups is found in the policies linked to the implementation of criminal justice. To provide an overview of the main issues we face within the system, it may be helpful for us to focus on three main branches where institutional failure is most apparent: policing, sentencing and prison systems. Starting with policing, some of its most discriminatory features can be seen in the execution of controversial policies like stop and search, which in recent years has been sold as a preventative measure to tackle knife crime but has been critiqued for its disproportionate use against black minorities. Official figures reflect this disproportionality, where while there were 4 stop and searches for every 1,000 white people, there were 38 stop and searches for every 1,000 black people between April 2018 to March 2019 [4]. As “almost half of all stop and searches” were carried out in London by the Metropolitan police [5], it may be useful to focus our attention on the figures here. A 2019 briefing conducted by the Criminal Justice Alliance found that not only are black people over 9 times more likely to be searched than white people [6], but specifically in London, 43% of searches were of black people compared to the 35.5% of white people [7]. These numbers become more problematic when put into perspective; according to the 2011 census, black minorities only make up 13.3% of London's population while the white majority makes up 44.9% [8]. This level of disproportionality which has only increased in recent years is a clear indicator of the discriminatory handling of policies encouraged by our government, which have important implications on the treatment of ethnic minorities within our societal institutions. When policies made to serve and protect the public exclude certain sections of society to such a degree that they begin to work against them, we must ask ourselves why in order to identify the ways this can be prevented.

Perhaps what was more surprising about the above figures was the response by the MET police, who stated that youth from “African-Carribean” descent were simply more likely to be involved in knife crime, either as perpetrators or victims of it, to defend the disproportionately high searches of black people [9]. However, research by Dr. Krisztian Posch from the London School of Economics has proven otherwise, as once these figures were analysed, 30.5% of the searches of white people resulted in further action, compared to only 26.7% of the searches of black minorities [10]. Contrary to the MET police statement, these figures would suggest that youth with African-Carribean heritage are not inherently ‘more likely’ to be complicit in violence, and that the high search rates of black people could be another example of implicit racial biases that have penetrated our criminal justice system. The misuse of Section 60 acts as a clear example of the potential dangers of current implicit biases within our institutions, as they have the potential to allow negative associations of black people & violence to transform from prejudicial sentiments to discriminatory action. In addressing this issue, not only will policies made to protect our population finally include black communities rather than work against them, but it will also improve the effectiveness of these policies, as figures prove that knife crime has not been significantly affected by Section 60 [11], meaning that reforming its methods would only push it into a more positive direction.

Sentencing

Implicit biases within sentencing expose another form of institutional racism that obstructs the ability to ensure the equal treatment of BAME groups within our criminal justice system (CJS). A system that promises fair and just action should not lack in providing the same standard for BAME individuals, which recent reports have shown a trend towards in certain cases. The 2017 Lammy Review, an essential piece on the treatment of BAME groups within our CJS, called attention to the disproportionate level of sentencing of BAME individuals in cases of drug offences; “within drug offences, the odds of receiving a prison sentence were around 240% higher for BAME offenders, compared to white offenders” [12]. The potential role that implicit biases can have on influencing this level of disproportionality cannot be ignored as a leading cause of this issue, as there has not been enough research into the subject to fully discount it. As the report concluded, this figure is “deeply worrying,” which increases the need for more to be done to scrutinise sentencing decisions, in order to ensure that judgments remain fully impartial [13]. These numbers lead to us to question how far implicit biases motivate discriminatory treatment of BAME individuals, and why there is still a lack of any thorough examination of this issue. After repeated scrutiny of our sentencing system, ignoring such figures which potentially encourage the unjust treatment of BAME groups in our CJS translates into a form of neglect, which in itself shows a worrying attitude of indifference towards the outcomes of BAME individuals. It is important to reiterate here that many forms of institutional racism can be much harder to detect because they are less overt in nature and can thus be hidden in nuances like neglect, which in this case encourages the potentiality of BAME individuals being subjected to a subpar standard of justice. Ignoring high levels of disproportionality is not a way forward, and reveals the need for more research to be done in this area to understand how our sentencing system can better serve BAME groups, and what preventative measures can be put in place to obstruct the possible penetration of implicit biases into our justice system.

Prison systems

Implicit biases also seem to have encouraged the mistreatment of minorities within our prison systems, often leading to neglect of wellbeing, and exclusion from proper rehabilitative programmes. Starting with the former, the Lammy review stated that BAME offenders in both adult and youth estates experience differential treatment upon reception, with BAME individuals “less likely to be identified with problems such as learning difficulties or mental health concerns” [14]. This is worrying, considering the proportion of “damaged” BAME individuals who require additional support in order for rehabilitative programs to be fully effective; “in the youth estate, 33% arrive with mental health problems, whilst a similar proportion presents with learning difficulties...45% arrive with substance misuse problems and 61% have a track record of disengagement with education” [15]. This is also a similar reality for those offenders in the adult estate; “an estimated 62% of men and 57% of women prisoners have a personality disorder, while 32% of new prisoners were recorded or self-identified as having a learning difficulty or disability. Many have been both victims and perpetrators of violence, with resulting trauma and psychological damage” [16]. The report concluded that “a far more comprehensive approach to assessing prisoners’ health, education and psychological state” [17] upon reception was required to adequately support BAME individuals.

In order to comprehend the potential negative outcomes of their neglect upon entry while facing these difficulties, it is important to understand the purpose of prison systems. The central purpose of the prison system, in theory, is to serve as a rehabilitative institution which provides offenders with the support needed in order to become active members of society; their sole purpose is not to carry out punishment for the crimes committed, as this in the long term does little to prevent the rate of reoffense. It seems however, that there has only been an adoption of the latter purpose, as little has been done to combat these high rates of “trauma and psychological damage” for BAME groups who are being deprived of the very basic necessities that, at the same time, have been more readily available to white offenders. This would prove to be another example of the detrimental impact of ‘passive’ forms of institutional racism previously discussed, as by nature, neglect is intangible and often difficult to see at face value, requiring a more thorough examination which critics often fall short of, in order for it to be detected and prevented. Rehabilitation is difficult to achieve without working on a firm foundation to build its provisions off of; this is why actively ignoring the wellbeing of BAME individuals obstructs their ability to combat underlying issues which could be preventable or controlled, which then excludes them from the potential benefits of rehabilitative programmes, while also encouraging a more hostile attitude to develop and grow out of frustration towards the same institutions which claim to support them.

More blatant forms of institutional racism can be found in the differential treatment of BAME and white individuals who have committed similar offences. The report notes the significance of the type of regime that prisoners are put under, as it can largely determine how successful rehabilitation is; “high security prisons are focused overwhelmingly on preventing escape, while lower security prisons involve more freedom of movement and therefore more opportunity to provide a regime focussed on rehabilitation” [18]. The report’s findings in regards to this were worrisome, as it showed that BAME males were proportionally much more likely to be put into high security prisons than white males who committed similar kinds of offences; for public order offences, 417 black offenders and 631 Asian offenders were placed in high security prisons for every 100 white offenders [19]. Overt discrimination that makes ethnicity a variable in the level of punishment an individual receives, reflects negatively on the current standard of our prison system and points to how ingrained biases are within it, allowing clear proofs of discrimination to be disregarded. One of the most prominent issues with institutional racism is not only its existence in the period in which it is being analysed, but also its long term effects, which not only stifles the progression of BAME Individuals for years to come, but more generally cements a culture of hostility between institutions and those subject to them. Wrongfully putting individuals into high security prisons, an environment that fosters hostility and lacks focus on rehabilitation, not only creates an atmosphere of scepticism from bottom-up, but also allows the neglect of preventable issues that encourage rates of reoffense to go unnoticed from top-down, which incites antagonism between prison staff and prisoners who as a result feel mistreated. The report touched on the issues of the ever-growing “them and us” culture which has severely impeded on the effectiveness of rehabilitative programmes, as it has led to a general disenchantment with the institution as a whole, including its branches of support that are increasingly being viewed with scepticism. Considering this, improving the treatment of BAME individuals would not only help combat the rate of reoffense, but it would also help tackle the growing culture of distrust and apathy between institutions and the people they are supposed to serve which is contributing to the ineffectiveness of rehabilitation.

Institutional racism within healthcare